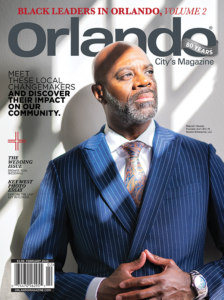

Learn About Orlando Magazine’s Founder and Early Years

The First Years of Orlando Magazine and a City Coming Into Its Own.

The City of Orlando has undergone massive change in the past century. Above: a view of downtown Orlando and Interstate 4.Photo by Roberto Gonzalez.

PICTURE THIS: IT IS THE 1940S, and Orlando was still learning how to introduce itself.

It was a city defined less by spectacle than by routine; one defined by citrus trucks rumbling down brick streets, by church bells on Sunday mornings, by lake water shimmering in the late afternoon sun. Winters brought visitors, but they arrived quietly, staying in modest hotels or boarding houses, content with fishing guides, warm afternoons, and the novelty of palm trees. Orlando was not yet selling fantasy. It was selling Florida as it actually was.

And in 1946, a newspaper advertising salesman named Hugh Waters decided that story deserved a magazine.

Rutland’s on Orange Avenue in Downtown Orlando. Copyright Historical Society of Central Florida, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Hugh Waters Takes the Leap

Waters had spent years selling advertisements for newspapers, learning not just how to pitch space on a page but how local economies worked—who needed customers, when tourism mattered, and how seasonal rhythms shaped business decisions. By the end of World War II, he sensed an opportunity.

Central Florida had a small but reliable influx of winter visitors. They needed information. Where to go. What to see. Where to worship. Where to fish. And local businesses needed a way to reach them directly.

Waters quit his job and launched The Orlando Attraction, a digest-sized weekly publication produced from November through April. It was not ambitious in scale, but it was precise in purpose. Each issue ran roughly 20 to 30 pages and functioned as a hybrid travel guide, local directory, and community snapshot.

The magazine was assembled and operated out of a garage apartment. Hugh and his wife, Olivia Brady Waters, sold every advertisement themselves. There was no sales team, no editorial staff, no design department. The average ad cost $3.75—affordable enough for small businesses, yet just enough to keep the presses running.

The risk was real. Printing costs were fixed. Distribution required coordination. And Orlando’s economy, while steady, was not booming. But Waters believed the city was worth documenting, and that belief proved contagious.

Olivia Brady Waters: The Magazine’s Creative Backbone

While Hugh handled sales and logistics, Olivia was integral to the magazine’s identity and survival. A co-founder in every meaningful sense, she brought artistic training, editorial sensibility, and organizational discipline to the operation.

Olivia was an accomplished artist who studied under Hal McIntosh, a respected figure in Florida’s art community. Her eye for composition and clarity influenced the magazine’s presentation at a time when layout was done by hand; literally cut, pasted, and arranged before plates were made. She was also a past member of the PEO Society, reflecting her deep engagement with civic and cultural life.

Beyond publishing, Olivia co-owned the Maggie Waters Shop in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, demonstrating a creative entrepreneurship that extended well beyond Orlando. She lived in Central Florida until her death in 2002, witnessing the city—and the magazine she helped create—transform beyond anything imaginable in 1946.

A bird’s eye view looking north along Orange Avenue and Church Street in downtown Orlando, Florida, circa 1957. opyright Historical Society of Central Florida, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Orlando in the 1940s: Life Between Groves and Lakes

To understand the early years of The Orlando Attraction is to understand Orlando itself in the 1940s—a city balanced between agrarian tradition and postwar possibility.

Citrus was still the dominant industry. Vast groves covered land that would later hold subdivisions, shopping centers, and expressways. Seasonal labor shaped the economy, and weather dictated prosperity. A hard freeze could devastate livelihoods overnight.

Downtown Orlando was compact and personal. Retail stores closed early. Movie theaters served as social anchors. Dining out was an event, not a habit. Many homes lacked air conditioning, relying instead on cross-breezes, screened porches, and ceiling fans. Summer heat slowed everything down.

Transportation was local. Interstates did not yet exist. Visitors arrived by train or drove two-lane highways. The idea of Orlando as a global destination was decades away. Tourism existed, but it was polite and unassuming.

The Orlando Attraction mirrored this world. Its tone was practical, welcoming, and grounded. It didn’t invent a lifestyle; it recorded one.

How Magazines Were Made in the 1940s

Producing a magazine in the 1940s was a fundamentally physical process—labor-intensive, mechanical, and unforgiving of mistakes.

There were no computers, no desktop publishing software, no digital photography. Type was set by hand or with linotype machines, casting molten metal into lines of text. Headlines, body copy, and advertisements all had to be measured precisely to fit the page. If an ad changed size, the entire layout had to be reworked.

Photographs, when used at all, were black and white, reproduced using halftone screens. Color printing was rare and expensive, typically reserved for covers of national magazines. For a small publication like The Orlando Attraction, color was simply not an option.

Layouts were assembled manually. Pages were mocked up using physical type galleys, wax, knives, and rulers. Once approved, metal plates were created for the printing press. Any error discovered after plating meant additional cost, something Hugh and Olivia Waters could ill afford.

Printing itself required coordination with local presses, careful scheduling, and upfront payment. Paper quality varied based on availability and cost. Postwar shortages still affected supply chains. Every issue represented a financial gamble.

That The Orlando Attraction appeared week after week was no small feat. It required discipline, accuracy, and relentless attention to detail. The magazine’s survival was as much a testament to operational skill as creative vision.

Mark Manfredi works on construction of The Vue, a 36 story condominium project in Orlando in June of 2006. Photo by Roberto Gonzalez.

The Advertisers Who Believed

Early advertisers were not just customers; they were partners in a shared experiment.

Businesses like Cypress Gardens, Gary’s Duck Inn, Mount Vernon Inn, the San Juan and Angebilt hotels, and First National Bank of Orlando recognized that a publication aimed at winter visitors benefited the entire community. Their ads were simple—often just text and line art—but they carried weight.

Each advertisement represented confidence in Orlando’s future and in the idea that telling the city’s story had value.

From Seasonal Guide to Civic Institution

As Orlando grew, so did the publication. Over time, The Orlando Attraction evolved into Orlando Magazine, expanding beyond seasonal tourism to cover the people, businesses, culture, and issues shaping Central Florida year-round.

But the magazine’s foundation never changed. From its earliest days, it was about place; about documenting a city honestly, attentively, and with pride.

That mission, born in a garage apartment with $3.75 ads and hand-set type, continues today.

The original single story La Cantina Restaurant, pictured here in 1979. Copyright Historical Society of Central Florida, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Orlando Originals

Businesses Born in the 1940s—and Still Thriving

Linda’s La Cantina Steakhouse (1947): Founded as Edie and Rudy’s La Cantina, this beloved steakhouse has remained a family-run institution for generations. Known for hand-cut, house-aged steaks cooked on a steel flat grill, Linda’s La Cantina preserves an old-school dining experience that feels increasingly rare in modern Orlando.

Whitmire’s Furniture (1947): A longtime fixture in Orlando retail, Whitmire’s Furniture has furnished Central Florida homes for more than 75 years, adapting to changing tastes while maintaining a reputation for service and quality.

Morgan Appliances (1948): Family-owned since its founding on Church Street, Morgan Appliances has served generations of Orlando residents through decades of technological change.

Citrus Bowl (1946): Originally known as the Tangerine Bowl, the Citrus Bowl is the seventh-oldest collegiate bowl in the country. Since 1993 the bowl has hosted top teams from the Big Ten and Southeastern conferences.

The Red Wing Restaurant (1948): Originally built as a home before opening as a restaurant, The Red Wing remains a time capsule of Old Florida, known for hand-cut steaks, game meats, and a lodge-like atmosphere that feels untouched by time.